BLACK TIGER SHRIMP: MAINSTREAM TURNED NICHE

BLACK TIGER SHRIMP: MAINSTREAM TURNED NICHE

Source: shrimpinsights.com

My friends in Bangladesh are always so proud of their tigers. When talking about these tigers, they proudly say they actually have two tigers, both native to their country. The most famous one is the Bengali tiger, whose habitat is the famous Sundarbans forest. The lesser known of the two is the black tiger shrimp (P. monodon), which is locally known as Bagda. As shrimp lovers, we all know that black tiger shrimp is one of its kind. It has a delicious flavor, a fantastic appearance and it is often naturally farmed. Naturally farmed means that it is produced in large ponds at very low densities and no or little commercial feed or other inputs such as antibiotics are used. Despite these unique selling points, due to the increased availability of cheaper L. vannamei shrimp, farmers struggle to get the right price for their product. In this blog I will update you regarding the status of black tiger shrimp production and markets and hope to remind you that the producers of this unique species deserve a special place in the market.

BLACK TIGER SHRIMP PRODUCTION LIKELY TO BE AROUND 450,000 MT

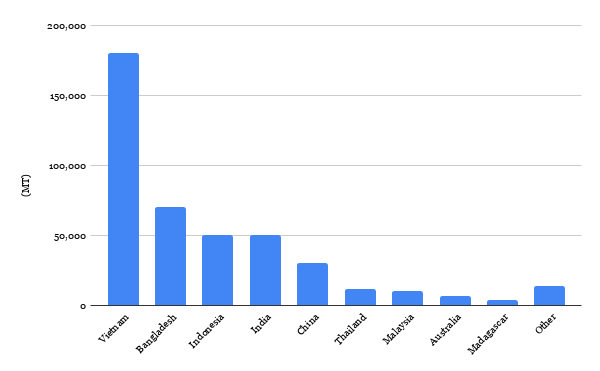

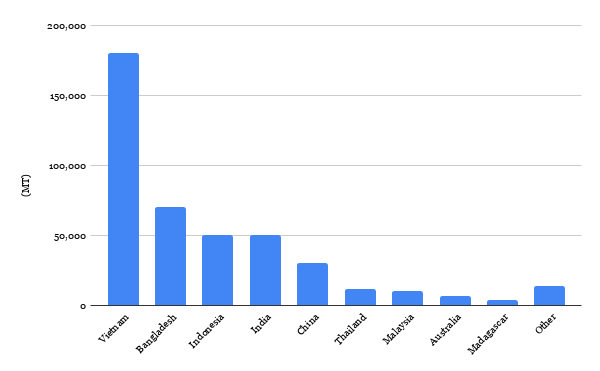

According to the FAO, global black tiger shrimp production in 2018 would have been around 750,000 MT. I personally find this figure to be a bit overestimated. Some of the leading shrimp feed suppliers in Asia would agree, and argue that the FAO’s figure might be more than double the actual amount. Their estimation is a figure closer to 350,000 MT. There’s a chance that these feed companies underestimate the figures, though, as they use estimations of feed sales as one of the indicators of production while most of the black tiger shrimp is in fact produced without much commercial feed. The actual figure is likely somewhere between the FAO’s 750,000 MT and the 350,000 MT calculated by some of the feed companies. I estimate that total black tiger shrimp production in 2018 reached around 450,000 MT.

Figure 1: Estimate of black tiger shrimp production per country

Source: Shrimp Insights estimate

Vietnam is the world’s largest producer of black tiger shrimp, followed by Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, China and other smaller producers such as the Philippines, Myanmar and Madagascar (Figure 1). Within the countries, the farmers cultivate black tiger shrimp on large areas of land which were previously mangrove forests or former rice fields. Nowadays, little or no mangroves are deforested at the cost of extensive shrimp farming expansion because this is often not regarded as a big economic opportunity and, more importantly, much of the remaining mangrove forest is luckily protected from deforestation by local government regulation. Farmers in these geographies often don’t have another choice than to grow black tiger shrimp or other brackish water species because rising sea levels prevent them from growing freshwater crops or freshwater fish species. Farmers in these geographies depend on black tiger shrimp for their livelihoods.

ALMOST ALL BLACK TIGER SHRIMP IS PRODUCED IN EXTENSIVE SYSTEMS

While black tiger shrimp is globally recognized for its premium flavor and appearance as well as for the large sizes in which it is sold, the species has another feature. These days, almost all black tiger shrimp are naturally farmed. Although there might still be some pockets of semi-intensive black tiger shrimp producers in countries like Malaysia and China, most of the farmers who used to cultivate black tiger shrimp in semi-intensive ponds now farm L. vannamei shrimp in those same ponds. From Cà Mau in Vietnam, to Khulna in Bangladesh, Kalimantan in Indonesia, West Bengal and Kerala in India, and Rakhine in Myanmar, almost all black tiger shrimp is now cultivated in extensive ponds.

Figure 2: Drone shot of extensive shrimp ponds close to Khulna, Bangladesh

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

These ponds are multiple hectares large and were traditionally, often already since the 1970s or 1980s, used as “trap and hold” systems. Water would be taken in according to the moon cycle and wild shrimp travelling to the mangroves to breed would be trapped inside the pond and grown for several months until they reached harvest size. When the shrimp would start circling in the pond during the full moon and new moon, farmers would use bamboo traps to catch the shrimp and sell it to a collector who would bring the shrimp to the marketplace.

Nowadays, most extensive black tiger shrimp farmers complement the trapped shrimp with additional post-larvae from hatcheries that often still use wild-caught broodstock. Due to the very low stocking densities, most of the farmers do not use commercial feed but allow the shrimp to grow on what’s present in the pond combined with some raw ingredients such as rice bran. Antibiotics or other medicines are rarely used. When harvested from these extensive ponds, the product is a naturally farmed free range shrimp.

Harvest volumes typically range from a few hundred kilograms to a thousand kilograms per hectare per year. While in some geographies corporate farmers play an important role (e.g. in Kalimantan, Indonesia and in Madagascar), in most geographies black tiger shrimp farming is dominated by small-scale farmers and their families who depend on the production of the species for their livelihoods.

Figure 3: Small-scale farmers in Bangladesh harvesting shrimp from their pond

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Although the story of small-scale producers depending on black tiger shrimp for their livelihoods is a great one to tell, in the market place their status as small-scale farmers is also a bottleneck for expansion. Many retailers in established markets such as the EU and US ask for ASC or BAP certification. However, for small-scale producers these certification schemes are too costly. Therefore, the black tiger shrimp currently sold to these retail markets is sourced from the corporate farms (or the few Vietnamese cooperatives) who have the required certification.

CURRENT PRODUCER/MARKET COMBINATIONS

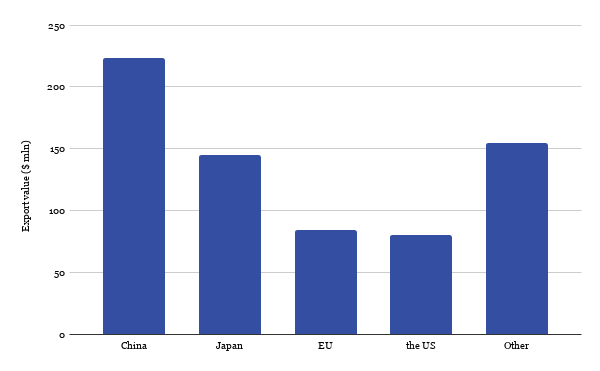

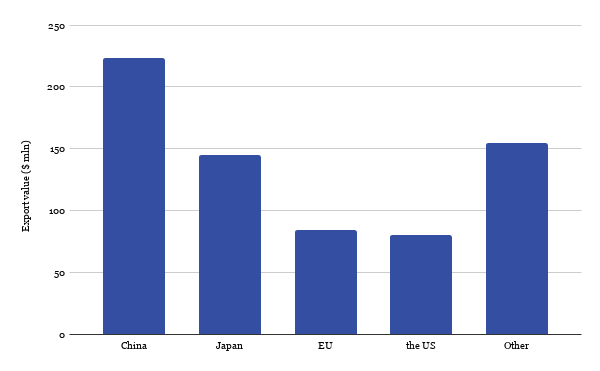

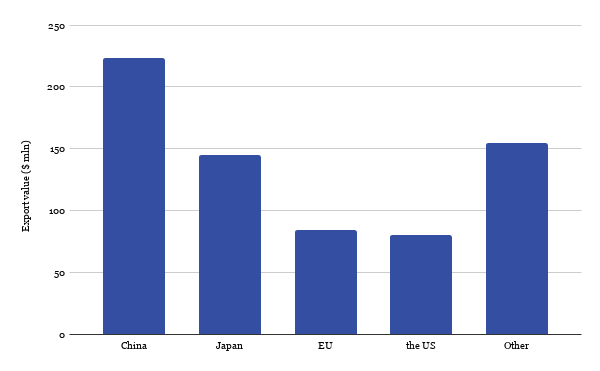

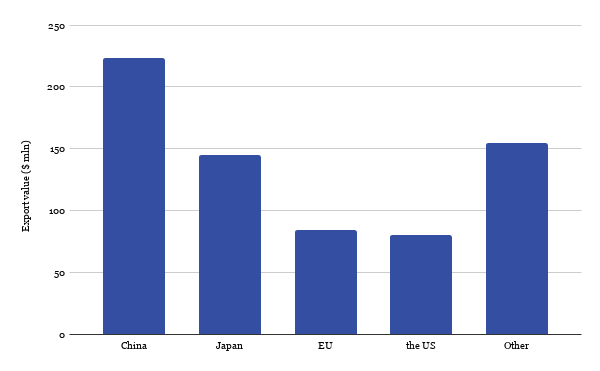

If we look at the most important markets for Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Madagascar, we see that each producer has found its own niche (Figures 4-6). Each producer/market combination seems to be based on geographical location, historical ties and/or supply chain conditions.

In 2019, Vietnam exported $687m black tiger shrimp. Vietnam sells most of its black tiger shrimp to China and Japan, which both genuinely appreciate the species for its premium market features such as its dark color and flavor but also the large sizes in which it can be produced. The EU and the US follow at third and fourth place. In the EU, Vietnam sells mainly to the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. These three countries represent about 70% of all exports from Vietnam to the EU and, as we will also see from Bangladesh’s export markets, are the heart of the black tiger shrimp market in the EU. Other markets which make up for the remainder of Vietnam’s exports are France and the UK.

While Vietnam competes with Bangladesh in the food service segment in the EU, in the retail segment it has a strong position and is not confronted with any significant competition. This is mainly due to the fact that Vietnam is the only country with a significant number of black tiger shrimp suppliers with ASC certification. Earlier this year, there were 12 certified semi-intensive producers (most of which likely no longer produce black tiger shrimp but have switched to L. vannamei) and 9 certified extensive black tiger shrimp producers. These certified suppliers are a mix of larger corporate farms on one hand and farmers’ cooperatives on the other. Jointly, these producers can supply more than 8,000 MT of ASC certified black tiger shrimp, which is more than any other country in the world.

In the US, importers and their customers seem to have largely lost their appetite for black tiger shrimp. Vietnam’s export value to the US halved from more than $160m in 2015 to below $80m in 2019. Vietnam’s market share has not been taken by other black tiger shrimp suppliers but is most likely lost to cheaper L. vannamei shrimp.

Figure 4: Vietnam’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Image

Source: VASEP

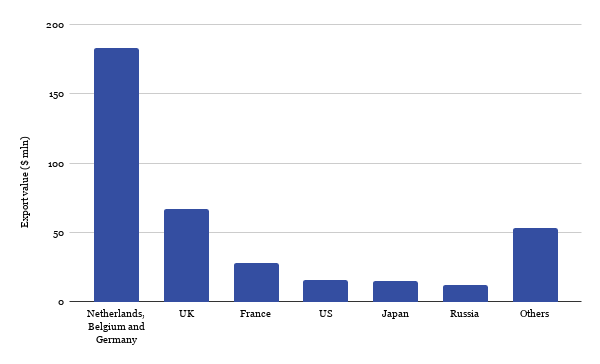

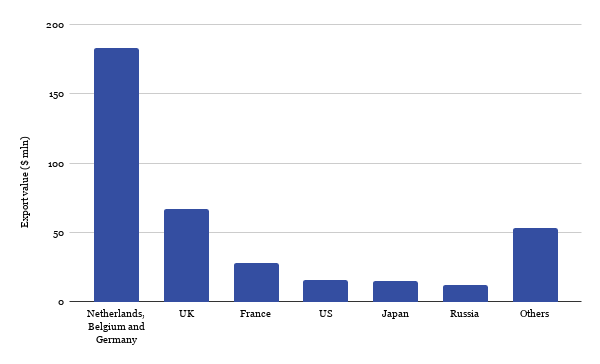

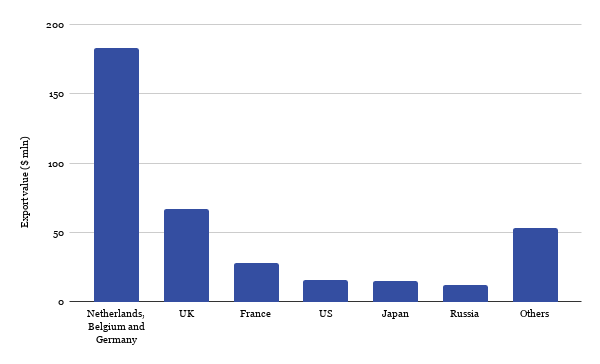

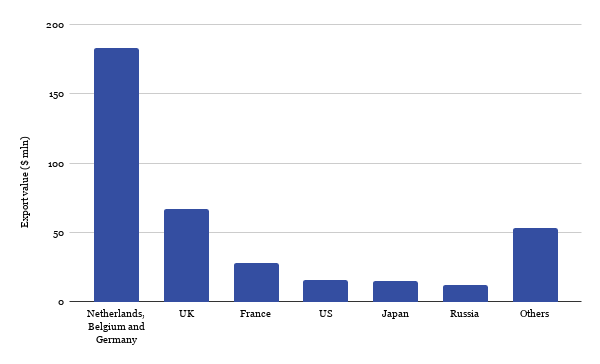

In 2019, Bangladesh exported around $375m black tiger shrimp. While Bangladesh has been faced with reduced raw material supply over the last few years, it still is one of the world’s leading black tiger shrimp exporters. Contrary to Vietnam, Bangladesh sells most of its shrimp to Europe (Figure 5).

Just like for Vietnam, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany are the largest markets in the EU for Bangladesh. Combined, the three countries account for 50% of Bangladesh’s total exports, and for around 75% of Bangladesh’s exports to the EU. The UK and France are the second and third largest markets in the EU. Black tiger shrimp from Bangladesh is mainly a food service product in the EU due to the requirement for ASC certification in the retail segment.

One of Bangladesh’s major challenges is the length and fragmentation of its supply chain. Due to the small harvest volumes of individual farmers, the product often changes ownership multiple times before it reaches the factory. The time it takes from harvest to processing and the lack of proper product handling along the supply chain is long and cause much of the product to not be of HOSO or HLSO quality. The lack of quality (i.e. freshness) of the final product may be one of the challenges for entering the market in Chinese and Japanese black tiger shrimp markets.

While Bangladesh has made major investments in the shrimp supply chain to overcome these issues, the existing market perception, the absence of market leaders such as Vietnamese company Minh Phu, and the lack of a coordinated marketing campaign makes that, for now, Bangladesh remains extremely dependent on the EU market for peeled black tiger shrimp.

Figure 5: Bangladesh’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Source: ITC Trade Map

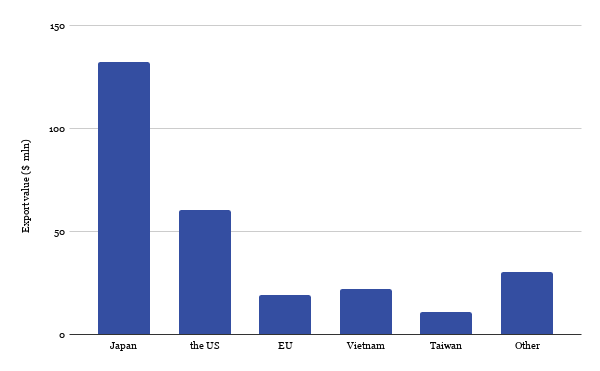

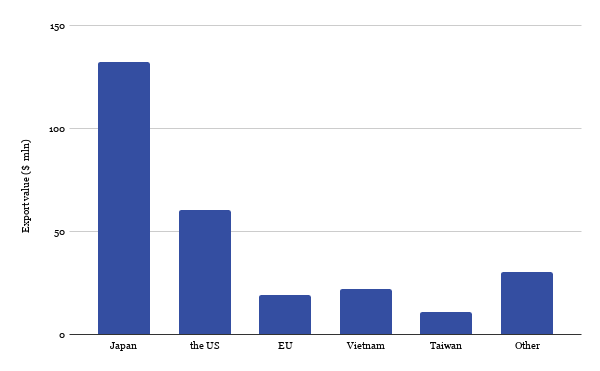

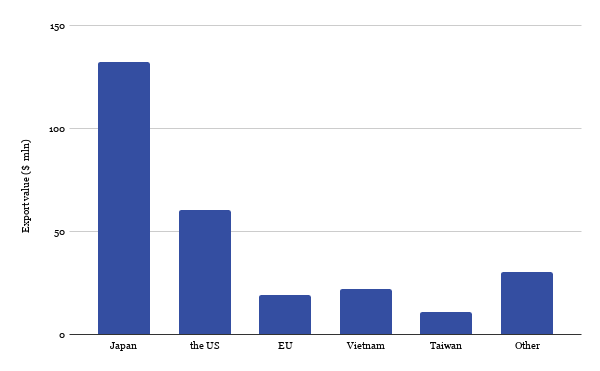

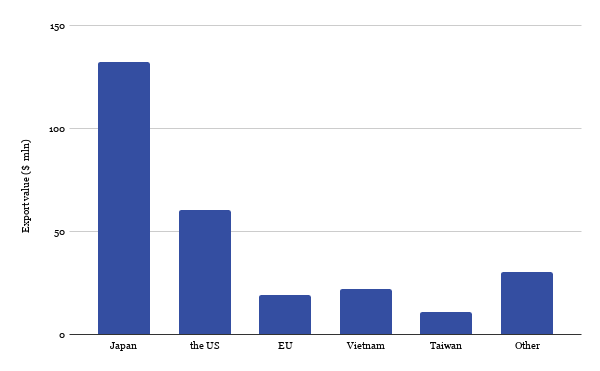

Unfortunately, Indonesia stopped reporting its exports per species in 2016, but I assume that the market distribution of its black tiger shrimp exports won’t have changed much since then, due to its continuing close trading relationship with Japan (Figure 6). Only the US might have declined, bearing in mind the decreased black tiger shrimp exports to the US from Vietnam and Bangladesh, but I expect the other markets to have remained fairly stable.

Black tiger shrimp in Indonesia is produced mainly by large corporate farmers in Kalimantan who own large pieces of land and are often vertically integrated due to also owning a processing plant. The independent farms in Indonesia are often larger than those in other countries. However, the production density is extremely low, most likely one of the lowest in Asia. Some black tiger shrimp is also produced in smaller ponds on Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi, where farmers stock black tiger shrimp together with fish or rice.

Indonesian black tiger shrimp producers have historically had a long relationship with Japanese seafood traders who would often invest in Kalimantan’s and Java’s largest black tiger shrimp producers through joint venture partnerships. The Japanese companies sell Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp as a premium product based on its freshness, large size, dark color and strong flavor.

This strong tie to the Japanese market means that Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp exporters are not very active in other markets and, with no anticipated growth of production, are unlikely to compete for other markets soon. This said, some of the producers in Kalimantan have recently obtained BAP and/or organic certification and are likely to start competing for premium black tiger shrimp markets in the EU and US.

Figure 6: Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2016

Source: ITC Trade Map

CONCLUSION

Some people hope for a revival of the black tiger shrimp farming industry. Worries about the price levels and oversupply of L. vannamei will likely cause some farmers in countries like India to start stocking several ponds with black tiger shrimp. Improvements in black tiger shrimp genetics by companies like Moana Technologies in Hawaii and CPF in Thailand have resulted in more disease tolerance and better growth, which would support this revival. However, even so, it is unlikely that black tiger shrimp will once again become a mainstream product.

As a niche product, black tiger shrimp still serves the needs of a significant group of chefs and consumers for whom it is the species of choice. Ecuador’s L. vannamei producers proudly claim to have #thebestshrimpintheworld. I hope that Asia’s black tiger shrimp producers realize that they could actually compete for this claim and, while doing so, can consolidate and expand the niche market for their premium product. However, they will need to start telling a collective story. By telling this unique story, they can better secure the livelihoods of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who depend on black tiger shrimp.

Figure 7: Bangladeshi farmer holding black tiger shrimp

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Readers' opinions

Other news

- A recovery for the shrimp market? 17/04/2024

- Shrimp market: Fear of inflation and declining demand 22/10/2022

- Summer demand remains strong in the United States of America and Europe 08/11/2021

- Global supply chains are being battered by fresh COVID surges 18/08/2021

- Animal Health and Welfare in Aquaculture 17/08/2021

- Pangasius Imports Outpacing Tilapia 10/08/2021

- Growth in India's Shrimp Production and Exports 08/08/2021

- Decline in shrimp exports to China makes shrimps cheaper in India for domestic market 03/08/2021

- Rabobank sees plenty of positives for both shrimp and salmon sectors 29/07/2021

- Asia’s Shrimp Connoisseurs: Japan, Taiwan And South Korea 02/07/2021

According to the FAO, global black tiger shrimp production in 2018 would have been around 750,000 MT. I personally find this figure to be a bit overestimated. Some of the leading shrimp feed suppliers in Asia would agree, and argue that the FAO’s figure might be more than double the actual amount. Their estimation is a figure closer to 350,000 MT. There’s a chance that these feed companies underestimate the figures, though, as they use estimations of feed sales as one of the indicators of production while most of the black tiger shrimp is in fact produced without much commercial feed. The actual figure is likely somewhere between the FAO’s 750,000 MT and the 350,000 MT calculated by some of the feed companies. I estimate that total black tiger shrimp production in 2018 reached around 450,000 MT.

Figure 1: Estimate of black tiger shrimp production per country

Source: Shrimp Insights estimate

Vietnam is the world’s largest producer of black tiger shrimp, followed by Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, China and other smaller producers such as the Philippines, Myanmar and Madagascar (Figure 1). Within the countries, the farmers cultivate black tiger shrimp on large areas of land which were previously mangrove forests or former rice fields. Nowadays, little or no mangroves are deforested at the cost of extensive shrimp farming expansion because this is often not regarded as a big economic opportunity and, more importantly, much of the remaining mangrove forest is luckily protected from deforestation by local government regulation. Farmers in these geographies often don’t have another choice than to grow black tiger shrimp or other brackish water species because rising sea levels prevent them from growing freshwater crops or freshwater fish species. Farmers in these geographies depend on black tiger shrimp for their livelihoods.

ALMOST ALL BLACK TIGER SHRIMP IS PRODUCED IN EXTENSIVE SYSTEMS

While black tiger shrimp is globally recognized for its premium flavor and appearance as well as for the large sizes in which it is sold, the species has another feature. These days, almost all black tiger shrimp are naturally farmed. Although there might still be some pockets of semi-intensive black tiger shrimp producers in countries like Malaysia and China, most of the farmers who used to cultivate black tiger shrimp in semi-intensive ponds now farm L. vannamei shrimp in those same ponds. From Cà Mau in Vietnam, to Khulna in Bangladesh, Kalimantan in Indonesia, West Bengal and Kerala in India, and Rakhine in Myanmar, almost all black tiger shrimp is now cultivated in extensive ponds.

Figure 2: Drone shot of extensive shrimp ponds close to Khulna, Bangladesh

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

These ponds are multiple hectares large and were traditionally, often already since the 1970s or 1980s, used as “trap and hold” systems. Water would be taken in according to the moon cycle and wild shrimp travelling to the mangroves to breed would be trapped inside the pond and grown for several months until they reached harvest size. When the shrimp would start circling in the pond during the full moon and new moon, farmers would use bamboo traps to catch the shrimp and sell it to a collector who would bring the shrimp to the marketplace.

Nowadays, most extensive black tiger shrimp farmers complement the trapped shrimp with additional post-larvae from hatcheries that often still use wild-caught broodstock. Due to the very low stocking densities, most of the farmers do not use commercial feed but allow the shrimp to grow on what’s present in the pond combined with some raw ingredients such as rice bran. Antibiotics or other medicines are rarely used. When harvested from these extensive ponds, the product is a naturally farmed free range shrimp.

Harvest volumes typically range from a few hundred kilograms to a thousand kilograms per hectare per year. While in some geographies corporate farmers play an important role (e.g. in Kalimantan, Indonesia and in Madagascar), in most geographies black tiger shrimp farming is dominated by small-scale farmers and their families who depend on the production of the species for their livelihoods.

Figure 3: Small-scale farmers in Bangladesh harvesting shrimp from their pond

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Although the story of small-scale producers depending on black tiger shrimp for their livelihoods is a great one to tell, in the market place their status as small-scale farmers is also a bottleneck for expansion. Many retailers in established markets such as the EU and US ask for ASC or BAP certification. However, for small-scale producers these certification schemes are too costly. Therefore, the black tiger shrimp currently sold to these retail markets is sourced from the corporate farms (or the few Vietnamese cooperatives) who have the required certification.

CURRENT PRODUCER/MARKET COMBINATIONS

If we look at the most important markets for Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Madagascar, we see that each producer has found its own niche (Figures 4-6). Each producer/market combination seems to be based on geographical location, historical ties and/or supply chain conditions.

In 2019, Vietnam exported $687m black tiger shrimp. Vietnam sells most of its black tiger shrimp to China and Japan, which both genuinely appreciate the species for its premium market features such as its dark color and flavor but also the large sizes in which it can be produced. The EU and the US follow at third and fourth place. In the EU, Vietnam sells mainly to the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. These three countries represent about 70% of all exports from Vietnam to the EU and, as we will also see from Bangladesh’s export markets, are the heart of the black tiger shrimp market in the EU. Other markets which make up for the remainder of Vietnam’s exports are France and the UK.

While Vietnam competes with Bangladesh in the food service segment in the EU, in the retail segment it has a strong position and is not confronted with any significant competition. This is mainly due to the fact that Vietnam is the only country with a significant number of black tiger shrimp suppliers with ASC certification. Earlier this year, there were 12 certified semi-intensive producers (most of which likely no longer produce black tiger shrimp but have switched to L. vannamei) and 9 certified extensive black tiger shrimp producers. These certified suppliers are a mix of larger corporate farms on one hand and farmers’ cooperatives on the other. Jointly, these producers can supply more than 8,000 MT of ASC certified black tiger shrimp, which is more than any other country in the world.

In the US, importers and their customers seem to have largely lost their appetite for black tiger shrimp. Vietnam’s export value to the US halved from more than $160m in 2015 to below $80m in 2019. Vietnam’s market share has not been taken by other black tiger shrimp suppliers but is most likely lost to cheaper L. vannamei shrimp.

Figure 4: Vietnam’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Image

Source: VASEP

In 2019, Bangladesh exported around $375m black tiger shrimp. While Bangladesh has been faced with reduced raw material supply over the last few years, it still is one of the world’s leading black tiger shrimp exporters. Contrary to Vietnam, Bangladesh sells most of its shrimp to Europe (Figure 5).

Just like for Vietnam, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany are the largest markets in the EU for Bangladesh. Combined, the three countries account for 50% of Bangladesh’s total exports, and for around 75% of Bangladesh’s exports to the EU. The UK and France are the second and third largest markets in the EU. Black tiger shrimp from Bangladesh is mainly a food service product in the EU due to the requirement for ASC certification in the retail segment.

One of Bangladesh’s major challenges is the length and fragmentation of its supply chain. Due to the small harvest volumes of individual farmers, the product often changes ownership multiple times before it reaches the factory. The time it takes from harvest to processing and the lack of proper product handling along the supply chain is long and cause much of the product to not be of HOSO or HLSO quality. The lack of quality (i.e. freshness) of the final product may be one of the challenges for entering the market in Chinese and Japanese black tiger shrimp markets.

While Bangladesh has made major investments in the shrimp supply chain to overcome these issues, the existing market perception, the absence of market leaders such as Vietnamese company Minh Phu, and the lack of a coordinated marketing campaign makes that, for now, Bangladesh remains extremely dependent on the EU market for peeled black tiger shrimp.

Figure 5: Bangladesh’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Source: ITC Trade Map

Unfortunately, Indonesia stopped reporting its exports per species in 2016, but I assume that the market distribution of its black tiger shrimp exports won’t have changed much since then, due to its continuing close trading relationship with Japan (Figure 6). Only the US might have declined, bearing in mind the decreased black tiger shrimp exports to the US from Vietnam and Bangladesh, but I expect the other markets to have remained fairly stable.

Black tiger shrimp in Indonesia is produced mainly by large corporate farmers in Kalimantan who own large pieces of land and are often vertically integrated due to also owning a processing plant. The independent farms in Indonesia are often larger than those in other countries. However, the production density is extremely low, most likely one of the lowest in Asia. Some black tiger shrimp is also produced in smaller ponds on Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi, where farmers stock black tiger shrimp together with fish or rice.

Indonesian black tiger shrimp producers have historically had a long relationship with Japanese seafood traders who would often invest in Kalimantan’s and Java’s largest black tiger shrimp producers through joint venture partnerships. The Japanese companies sell Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp as a premium product based on its freshness, large size, dark color and strong flavor.

This strong tie to the Japanese market means that Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp exporters are not very active in other markets and, with no anticipated growth of production, are unlikely to compete for other markets soon. This said, some of the producers in Kalimantan have recently obtained BAP and/or organic certification and are likely to start competing for premium black tiger shrimp markets in the EU and US.

Figure 6: Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2016

Source: ITC Trade Map

CONCLUSION

Some people hope for a revival of the black tiger shrimp farming industry. Worries about the price levels and oversupply of L. vannamei will likely cause some farmers in countries like India to start stocking several ponds with black tiger shrimp. Improvements in black tiger shrimp genetics by companies like Moana Technologies in Hawaii and CPF in Thailand have resulted in more disease tolerance and better growth, which would support this revival. However, even so, it is unlikely that black tiger shrimp will once again become a mainstream product.

As a niche product, black tiger shrimp still serves the needs of a significant group of chefs and consumers for whom it is the species of choice. Ecuador’s L. vannamei producers proudly claim to have #thebestshrimpintheworld. I hope that Asia’s black tiger shrimp producers realize that they could actually compete for this claim and, while doing so, can consolidate and expand the niche market for their premium product. However, they will need to start telling a collective story. By telling this unique story, they can better secure the livelihoods of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who depend on black tiger shrimp.

Figure 7: Bangladeshi farmer holding black tiger shrimp

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Readers' opinions

Other news

- A recovery for the shrimp market? 17/04/2024

- Shrimp market: Fear of inflation and declining demand 22/10/2022

- Summer demand remains strong in the United States of America and Europe 08/11/2021

- Global supply chains are being battered by fresh COVID surges 18/08/2021

- Animal Health and Welfare in Aquaculture 17/08/2021

- Pangasius Imports Outpacing Tilapia 10/08/2021

- Growth in India's Shrimp Production and Exports 08/08/2021

- Decline in shrimp exports to China makes shrimps cheaper in India for domestic market 03/08/2021

- Rabobank sees plenty of positives for both shrimp and salmon sectors 29/07/2021

- Asia’s Shrimp Connoisseurs: Japan, Taiwan And South Korea 02/07/2021

While black tiger shrimp is globally recognized for its premium flavor and appearance as well as for the large sizes in which it is sold, the species has another feature. These days, almost all black tiger shrimp are naturally farmed. Although there might still be some pockets of semi-intensive black tiger shrimp producers in countries like Malaysia and China, most of the farmers who used to cultivate black tiger shrimp in semi-intensive ponds now farm L. vannamei shrimp in those same ponds. From Cà Mau in Vietnam, to Khulna in Bangladesh, Kalimantan in Indonesia, West Bengal and Kerala in India, and Rakhine in Myanmar, almost all black tiger shrimp is now cultivated in extensive ponds.

Figure 2: Drone shot of extensive shrimp ponds close to Khulna, Bangladesh

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

These ponds are multiple hectares large and were traditionally, often already since the 1970s or 1980s, used as “trap and hold” systems. Water would be taken in according to the moon cycle and wild shrimp travelling to the mangroves to breed would be trapped inside the pond and grown for several months until they reached harvest size. When the shrimp would start circling in the pond during the full moon and new moon, farmers would use bamboo traps to catch the shrimp and sell it to a collector who would bring the shrimp to the marketplace.

Nowadays, most extensive black tiger shrimp farmers complement the trapped shrimp with additional post-larvae from hatcheries that often still use wild-caught broodstock. Due to the very low stocking densities, most of the farmers do not use commercial feed but allow the shrimp to grow on what’s present in the pond combined with some raw ingredients such as rice bran. Antibiotics or other medicines are rarely used. When harvested from these extensive ponds, the product is a naturally farmed free range shrimp.

Harvest volumes typically range from a few hundred kilograms to a thousand kilograms per hectare per year. While in some geographies corporate farmers play an important role (e.g. in Kalimantan, Indonesia and in Madagascar), in most geographies black tiger shrimp farming is dominated by small-scale farmers and their families who depend on the production of the species for their livelihoods.

Figure 3: Small-scale farmers in Bangladesh harvesting shrimp from their pond

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Although the story of small-scale producers depending on black tiger shrimp for their livelihoods is a great one to tell, in the market place their status as small-scale farmers is also a bottleneck for expansion. Many retailers in established markets such as the EU and US ask for ASC or BAP certification. However, for small-scale producers these certification schemes are too costly. Therefore, the black tiger shrimp currently sold to these retail markets is sourced from the corporate farms (or the few Vietnamese cooperatives) who have the required certification.

CURRENT PRODUCER/MARKET COMBINATIONS

If we look at the most important markets for Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Madagascar, we see that each producer has found its own niche (Figures 4-6). Each producer/market combination seems to be based on geographical location, historical ties and/or supply chain conditions.

In 2019, Vietnam exported $687m black tiger shrimp. Vietnam sells most of its black tiger shrimp to China and Japan, which both genuinely appreciate the species for its premium market features such as its dark color and flavor but also the large sizes in which it can be produced. The EU and the US follow at third and fourth place. In the EU, Vietnam sells mainly to the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. These three countries represent about 70% of all exports from Vietnam to the EU and, as we will also see from Bangladesh’s export markets, are the heart of the black tiger shrimp market in the EU. Other markets which make up for the remainder of Vietnam’s exports are France and the UK.

While Vietnam competes with Bangladesh in the food service segment in the EU, in the retail segment it has a strong position and is not confronted with any significant competition. This is mainly due to the fact that Vietnam is the only country with a significant number of black tiger shrimp suppliers with ASC certification. Earlier this year, there were 12 certified semi-intensive producers (most of which likely no longer produce black tiger shrimp but have switched to L. vannamei) and 9 certified extensive black tiger shrimp producers. These certified suppliers are a mix of larger corporate farms on one hand and farmers’ cooperatives on the other. Jointly, these producers can supply more than 8,000 MT of ASC certified black tiger shrimp, which is more than any other country in the world.

In the US, importers and their customers seem to have largely lost their appetite for black tiger shrimp. Vietnam’s export value to the US halved from more than $160m in 2015 to below $80m in 2019. Vietnam’s market share has not been taken by other black tiger shrimp suppliers but is most likely lost to cheaper L. vannamei shrimp.

Figure 4: Vietnam’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Image

Source: VASEP

In 2019, Bangladesh exported around $375m black tiger shrimp. While Bangladesh has been faced with reduced raw material supply over the last few years, it still is one of the world’s leading black tiger shrimp exporters. Contrary to Vietnam, Bangladesh sells most of its shrimp to Europe (Figure 5).

Just like for Vietnam, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany are the largest markets in the EU for Bangladesh. Combined, the three countries account for 50% of Bangladesh’s total exports, and for around 75% of Bangladesh’s exports to the EU. The UK and France are the second and third largest markets in the EU. Black tiger shrimp from Bangladesh is mainly a food service product in the EU due to the requirement for ASC certification in the retail segment.

One of Bangladesh’s major challenges is the length and fragmentation of its supply chain. Due to the small harvest volumes of individual farmers, the product often changes ownership multiple times before it reaches the factory. The time it takes from harvest to processing and the lack of proper product handling along the supply chain is long and cause much of the product to not be of HOSO or HLSO quality. The lack of quality (i.e. freshness) of the final product may be one of the challenges for entering the market in Chinese and Japanese black tiger shrimp markets.

While Bangladesh has made major investments in the shrimp supply chain to overcome these issues, the existing market perception, the absence of market leaders such as Vietnamese company Minh Phu, and the lack of a coordinated marketing campaign makes that, for now, Bangladesh remains extremely dependent on the EU market for peeled black tiger shrimp.

Figure 5: Bangladesh’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Source: ITC Trade Map

Unfortunately, Indonesia stopped reporting its exports per species in 2016, but I assume that the market distribution of its black tiger shrimp exports won’t have changed much since then, due to its continuing close trading relationship with Japan (Figure 6). Only the US might have declined, bearing in mind the decreased black tiger shrimp exports to the US from Vietnam and Bangladesh, but I expect the other markets to have remained fairly stable.

Black tiger shrimp in Indonesia is produced mainly by large corporate farmers in Kalimantan who own large pieces of land and are often vertically integrated due to also owning a processing plant. The independent farms in Indonesia are often larger than those in other countries. However, the production density is extremely low, most likely one of the lowest in Asia. Some black tiger shrimp is also produced in smaller ponds on Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi, where farmers stock black tiger shrimp together with fish or rice.

Indonesian black tiger shrimp producers have historically had a long relationship with Japanese seafood traders who would often invest in Kalimantan’s and Java’s largest black tiger shrimp producers through joint venture partnerships. The Japanese companies sell Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp as a premium product based on its freshness, large size, dark color and strong flavor.

This strong tie to the Japanese market means that Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp exporters are not very active in other markets and, with no anticipated growth of production, are unlikely to compete for other markets soon. This said, some of the producers in Kalimantan have recently obtained BAP and/or organic certification and are likely to start competing for premium black tiger shrimp markets in the EU and US.

Figure 6: Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2016

Source: ITC Trade Map

CONCLUSION

Some people hope for a revival of the black tiger shrimp farming industry. Worries about the price levels and oversupply of L. vannamei will likely cause some farmers in countries like India to start stocking several ponds with black tiger shrimp. Improvements in black tiger shrimp genetics by companies like Moana Technologies in Hawaii and CPF in Thailand have resulted in more disease tolerance and better growth, which would support this revival. However, even so, it is unlikely that black tiger shrimp will once again become a mainstream product.

As a niche product, black tiger shrimp still serves the needs of a significant group of chefs and consumers for whom it is the species of choice. Ecuador’s L. vannamei producers proudly claim to have #thebestshrimpintheworld. I hope that Asia’s black tiger shrimp producers realize that they could actually compete for this claim and, while doing so, can consolidate and expand the niche market for their premium product. However, they will need to start telling a collective story. By telling this unique story, they can better secure the livelihoods of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who depend on black tiger shrimp.

Figure 7: Bangladeshi farmer holding black tiger shrimp

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Readers' opinions

Other news

- A recovery for the shrimp market? 17/04/2024

- Shrimp market: Fear of inflation and declining demand 22/10/2022

- Summer demand remains strong in the United States of America and Europe 08/11/2021

- Global supply chains are being battered by fresh COVID surges 18/08/2021

- Animal Health and Welfare in Aquaculture 17/08/2021

- Pangasius Imports Outpacing Tilapia 10/08/2021

- Growth in India's Shrimp Production and Exports 08/08/2021

- Decline in shrimp exports to China makes shrimps cheaper in India for domestic market 03/08/2021

- Rabobank sees plenty of positives for both shrimp and salmon sectors 29/07/2021

- Asia’s Shrimp Connoisseurs: Japan, Taiwan And South Korea 02/07/2021

If we look at the most important markets for Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Madagascar, we see that each producer has found its own niche (Figures 4-6). Each producer/market combination seems to be based on geographical location, historical ties and/or supply chain conditions.

In 2019, Vietnam exported $687m black tiger shrimp. Vietnam sells most of its black tiger shrimp to China and Japan, which both genuinely appreciate the species for its premium market features such as its dark color and flavor but also the large sizes in which it can be produced. The EU and the US follow at third and fourth place. In the EU, Vietnam sells mainly to the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. These three countries represent about 70% of all exports from Vietnam to the EU and, as we will also see from Bangladesh’s export markets, are the heart of the black tiger shrimp market in the EU. Other markets which make up for the remainder of Vietnam’s exports are France and the UK.

While Vietnam competes with Bangladesh in the food service segment in the EU, in the retail segment it has a strong position and is not confronted with any significant competition. This is mainly due to the fact that Vietnam is the only country with a significant number of black tiger shrimp suppliers with ASC certification. Earlier this year, there were 12 certified semi-intensive producers (most of which likely no longer produce black tiger shrimp but have switched to L. vannamei) and 9 certified extensive black tiger shrimp producers. These certified suppliers are a mix of larger corporate farms on one hand and farmers’ cooperatives on the other. Jointly, these producers can supply more than 8,000 MT of ASC certified black tiger shrimp, which is more than any other country in the world.

In the US, importers and their customers seem to have largely lost their appetite for black tiger shrimp. Vietnam’s export value to the US halved from more than $160m in 2015 to below $80m in 2019. Vietnam’s market share has not been taken by other black tiger shrimp suppliers but is most likely lost to cheaper L. vannamei shrimp.

Figure 4: Vietnam’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Image

Source: VASEP

In 2019, Bangladesh exported around $375m black tiger shrimp. While Bangladesh has been faced with reduced raw material supply over the last few years, it still is one of the world’s leading black tiger shrimp exporters. Contrary to Vietnam, Bangladesh sells most of its shrimp to Europe (Figure 5).

Just like for Vietnam, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany are the largest markets in the EU for Bangladesh. Combined, the three countries account for 50% of Bangladesh’s total exports, and for around 75% of Bangladesh’s exports to the EU. The UK and France are the second and third largest markets in the EU. Black tiger shrimp from Bangladesh is mainly a food service product in the EU due to the requirement for ASC certification in the retail segment.

One of Bangladesh’s major challenges is the length and fragmentation of its supply chain. Due to the small harvest volumes of individual farmers, the product often changes ownership multiple times before it reaches the factory. The time it takes from harvest to processing and the lack of proper product handling along the supply chain is long and cause much of the product to not be of HOSO or HLSO quality. The lack of quality (i.e. freshness) of the final product may be one of the challenges for entering the market in Chinese and Japanese black tiger shrimp markets.

While Bangladesh has made major investments in the shrimp supply chain to overcome these issues, the existing market perception, the absence of market leaders such as Vietnamese company Minh Phu, and the lack of a coordinated marketing campaign makes that, for now, Bangladesh remains extremely dependent on the EU market for peeled black tiger shrimp.

Figure 5: Bangladesh’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2019

Source: ITC Trade Map

Unfortunately, Indonesia stopped reporting its exports per species in 2016, but I assume that the market distribution of its black tiger shrimp exports won’t have changed much since then, due to its continuing close trading relationship with Japan (Figure 6). Only the US might have declined, bearing in mind the decreased black tiger shrimp exports to the US from Vietnam and Bangladesh, but I expect the other markets to have remained fairly stable.

Black tiger shrimp in Indonesia is produced mainly by large corporate farmers in Kalimantan who own large pieces of land and are often vertically integrated due to also owning a processing plant. The independent farms in Indonesia are often larger than those in other countries. However, the production density is extremely low, most likely one of the lowest in Asia. Some black tiger shrimp is also produced in smaller ponds on Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi, where farmers stock black tiger shrimp together with fish or rice.

Indonesian black tiger shrimp producers have historically had a long relationship with Japanese seafood traders who would often invest in Kalimantan’s and Java’s largest black tiger shrimp producers through joint venture partnerships. The Japanese companies sell Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp as a premium product based on its freshness, large size, dark color and strong flavor.

This strong tie to the Japanese market means that Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp exporters are not very active in other markets and, with no anticipated growth of production, are unlikely to compete for other markets soon. This said, some of the producers in Kalimantan have recently obtained BAP and/or organic certification and are likely to start competing for premium black tiger shrimp markets in the EU and US.

Figure 6: Indonesia’s black tiger shrimp export markets in 2016

Source: ITC Trade Map

CONCLUSION

Some people hope for a revival of the black tiger shrimp farming industry. Worries about the price levels and oversupply of L. vannamei will likely cause some farmers in countries like India to start stocking several ponds with black tiger shrimp. Improvements in black tiger shrimp genetics by companies like Moana Technologies in Hawaii and CPF in Thailand have resulted in more disease tolerance and better growth, which would support this revival. However, even so, it is unlikely that black tiger shrimp will once again become a mainstream product.

As a niche product, black tiger shrimp still serves the needs of a significant group of chefs and consumers for whom it is the species of choice. Ecuador’s L. vannamei producers proudly claim to have #thebestshrimpintheworld. I hope that Asia’s black tiger shrimp producers realize that they could actually compete for this claim and, while doing so, can consolidate and expand the niche market for their premium product. However, they will need to start telling a collective story. By telling this unique story, they can better secure the livelihoods of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who depend on black tiger shrimp.

Figure 7: Bangladeshi farmer holding black tiger shrimp

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Readers' opinions

Some people hope for a revival of the black tiger shrimp farming industry. Worries about the price levels and oversupply of L. vannamei will likely cause some farmers in countries like India to start stocking several ponds with black tiger shrimp. Improvements in black tiger shrimp genetics by companies like Moana Technologies in Hawaii and CPF in Thailand have resulted in more disease tolerance and better growth, which would support this revival. However, even so, it is unlikely that black tiger shrimp will once again become a mainstream product.

As a niche product, black tiger shrimp still serves the needs of a significant group of chefs and consumers for whom it is the species of choice. Ecuador’s L. vannamei producers proudly claim to have #thebestshrimpintheworld. I hope that Asia’s black tiger shrimp producers realize that they could actually compete for this claim and, while doing so, can consolidate and expand the niche market for their premium product. However, they will need to start telling a collective story. By telling this unique story, they can better secure the livelihoods of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who depend on black tiger shrimp.

Figure 7: Bangladeshi farmer holding black tiger shrimp

Source: Solidaridad Bangladesh

Other news

- A recovery for the shrimp market? 17/04/2024

- Shrimp market: Fear of inflation and declining demand 22/10/2022

- Summer demand remains strong in the United States of America and Europe 08/11/2021

- Global supply chains are being battered by fresh COVID surges 18/08/2021

- Animal Health and Welfare in Aquaculture 17/08/2021

- Pangasius Imports Outpacing Tilapia 10/08/2021

- Growth in India's Shrimp Production and Exports 08/08/2021

- Decline in shrimp exports to China makes shrimps cheaper in India for domestic market 03/08/2021

- Rabobank sees plenty of positives for both shrimp and salmon sectors 29/07/2021

- Asia’s Shrimp Connoisseurs: Japan, Taiwan And South Korea 02/07/2021