INDIAN EXPORTS AND PRODUCTION IN 2020 SEVERELY HIT BUT OUTLOOK STILL BULLISH

- 1. SAP REPORTS 20% DROP IN SHRIMP PRODUCTION

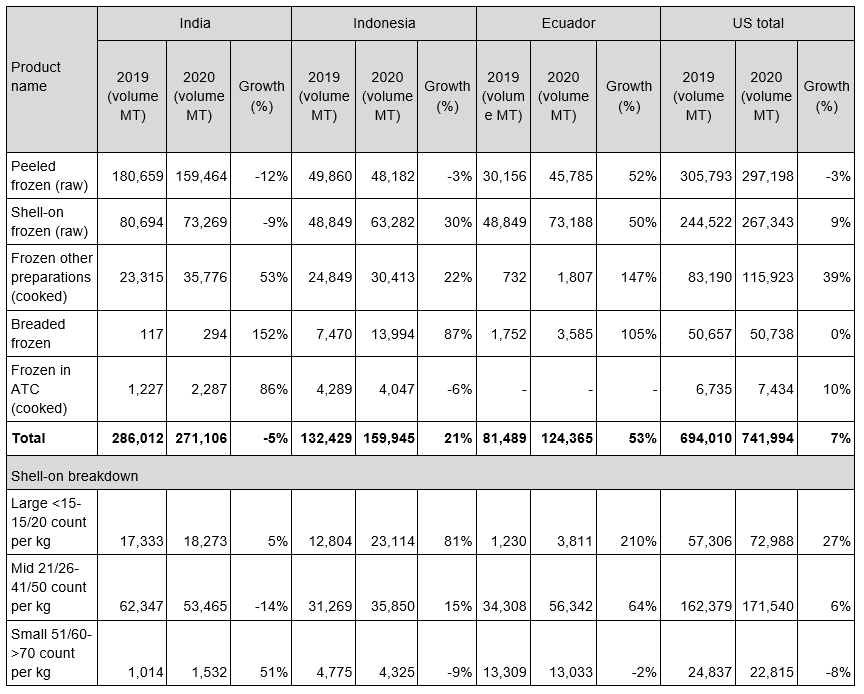

- 2. EXPORT VOLUME DOWN 14%: CHINA SEVERELY HIT, AND PRESSURE ON MARKET SHARE IN THE US

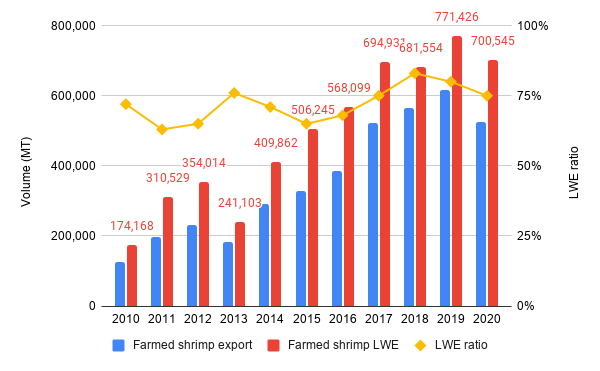

- 3. LWE CALCULATION: FARMED SHRIMP PRODUCTION DOWN ONLY 10%

- 4. SHORTER CROP CYCLES MEAN SMALLER SHRIMP AT HARVEST TIME

- 5. EXPORTS OF SMALLER SIZES TO CHINA: CHANGING INDIA’S SHRIMP INDUSTRY?

- 6. TOLERANT BROODSTOCK LINES: ENABLING A RETURN TO LARGER SIZES AND HIGHER DENSITIES?

- 7. CONCLUSION

INDIAN EXPORTS AND PRODUCTION IN 2020 SEVERELY HIT BUT OUTLOOK STILL BULLISH

Let’s dive straight in. India hasn’t managed to increase its shrimp output in 2020. Depending on the source, India’s production is believed to have dropped from the 2019 level of somewhere between 780,000 and 800,000 metric tons (MT) to anywhere between 650,000 and 700,000 MT in 2020. COVID-19 disruptions in the first part of the year and continuous disease issues that bothered farmers across the country throughout the whole of 2020 have had a severe impact on production. In this blog I want to reflect on the Society of Aquaculture Professionals’ (SAP) crop review, India’s 2020 export data, and a live weight equivalent (LWE) calculation, and I will share some thoughts about some structural changes that we might see in 2021 and beyond.

Many thanks to my friends at SAP, some of India’s leading exporters, and some other industry stakeholders in India for reviewing and discussing my observations before the publication of this blog post!

SAP REPORTS 20% DROP IN SHRIMP PRODUCTION

Production data is always challenging. In India, there are two common sources that provide production estimates at the national level: one is the Marine Products Export Development Authority (MPEDA); the other is SAP. SAP just released its 2020 crop review, which is based on surveys among, and discussions with, its broad member network in the Indian shrimp industry.

Figure 1: SAP’s production estimates from 2018 till 2020

Source: For the statistics concerning 2020: SAP data presented in its 2020 crop review; for the statistics concerning 2018 and 2019: SAP data presented at Aqua India 2020

SAP’s production estimates from 2019 and 2020 suggest that production in Odisha and West Bengal declined by 25% and 40% respectively. While stocking in both states would normally start in mid-February, the lockdown and the following shortage of post-larvae (PL) made farmers only stock the majority of their ponds by May or even June. Most farmers had two crops straight after each other or chose to only have one crop. In the second half of the year, disease reportedly heavily affected the farmers that chose to have a second crop. In my opinion, the drop in production in Odisha and West Bengal will be short lived; continuous expansion of farming areas in the two states gives enough reason to believe that production will increase over the next couple of years.

In the northern part of Andhra Pradesh (Srikakulam to Krishna), SAP reports production to have dropped between 10-20% depending on the district. In the southern districts (Guntur to Nellore), production actually increased. The decline in production in the northern parts of the state mainly occurred during the first half of the year when panic harvesting during the early stages of the lockdown and subsequent disruptions accounted for most of the production loss. Throughout the year, farmers struggled with disease but they adapted their strategies and, especially during the second half of the year, output in the northern part of the state drastically improved and maybe even outperformed the same period in 2019. In the southern districts, despite COVID-19 disruptions, due to improved rainfall during the first crop of 2020 the harvest of that crop outperformed 2019. The overall performance in the south was tempered during the second half of the year when cyclone Nivar caused damage and disease was more prevalent. Comparing the numbers of SAP’s 2020 and 2019 crop reviews suggests that total production in Andhra Pradesh may have dropped by as much as 25%.

While I'm not really surprised by SAP’s data for most of the states, the data presented for Gujarat is quite unexpected. SAP reports a strong decline in production from 55,000 MT in 2018, reducing to 45,000 in 2019, and then further to only 23,000 MT in 2020. According to SAP’s members, Gujarat’s decline in production is partly to be blamed on climate conditions and a COVID-19-related shortage of PL. But the main source of blame is the unregulated expansion of farming areas over the past decade that has led to the current context of various production issues. Yet Gujarat has often been mentioned as the largest expected contributor to India’s future shrimp output. At the Global Aquaculture Alliance Shrimp Session during the Boston Seafood Show in 2019, Elias Sait, the secretary general of the Seafood Exporters Association of India (SEAI), even mentioned that out of a possible increase in shrimp production of 450,000 MT by 2022 in India, Gujarat could contribute as much as 250,000 MT. If SAP is right and production in Gujarat more than halved since its peak in 2018, what remains of Gujarat’s promised contribution?

Production data is always challenging. In India, there are two common sources that provide production estimates at the national level: one is the Marine Products Export Development Authority (MPEDA); the other is SAP. SAP just released its 2020 crop review, which is based on surveys among, and discussions with, its broad member network in the Indian shrimp industry.

Figure 1: SAP’s production estimates from 2018 till 2020

Source: For the statistics concerning 2020: SAP data presented in its 2020 crop review; for the statistics concerning 2018 and 2019: SAP data presented at Aqua India 2020

SAP’s production estimates from 2019 and 2020 suggest that production in Odisha and West Bengal declined by 25% and 40% respectively. While stocking in both states would normally start in mid-February, the lockdown and the following shortage of post-larvae (PL) made farmers only stock the majority of their ponds by May or even June. Most farmers had two crops straight after each other or chose to only have one crop. In the second half of the year, disease reportedly heavily affected the farmers that chose to have a second crop. In my opinion, the drop in production in Odisha and West Bengal will be short lived; continuous expansion of farming areas in the two states gives enough reason to believe that production will increase over the next couple of years.

In the northern part of Andhra Pradesh (Srikakulam to Krishna), SAP reports production to have dropped between 10-20% depending on the district. In the southern districts (Guntur to Nellore), production actually increased. The decline in production in the northern parts of the state mainly occurred during the first half of the year when panic harvesting during the early stages of the lockdown and subsequent disruptions accounted for most of the production loss. Throughout the year, farmers struggled with disease but they adapted their strategies and, especially during the second half of the year, output in the northern part of the state drastically improved and maybe even outperformed the same period in 2019. In the southern districts, despite COVID-19 disruptions, due to improved rainfall during the first crop of 2020 the harvest of that crop outperformed 2019. The overall performance in the south was tempered during the second half of the year when cyclone Nivar caused damage and disease was more prevalent. Comparing the numbers of SAP’s 2020 and 2019 crop reviews suggests that total production in Andhra Pradesh may have dropped by as much as 25%.

While I'm not really surprised by SAP’s data for most of the states, the data presented for Gujarat is quite unexpected. SAP reports a strong decline in production from 55,000 MT in 2018, reducing to 45,000 in 2019, and then further to only 23,000 MT in 2020. According to SAP’s members, Gujarat’s decline in production is partly to be blamed on climate conditions and a COVID-19-related shortage of PL. But the main source of blame is the unregulated expansion of farming areas over the past decade that has led to the current context of various production issues. Yet Gujarat has often been mentioned as the largest expected contributor to India’s future shrimp output. At the Global Aquaculture Alliance Shrimp Session during the Boston Seafood Show in 2019, Elias Sait, the secretary general of the Seafood Exporters Association of India (SEAI), even mentioned that out of a possible increase in shrimp production of 450,000 MT by 2022 in India, Gujarat could contribute as much as 250,000 MT. If SAP is right and production in Gujarat more than halved since its peak in 2018, what remains of Gujarat’s promised contribution?